A Polysaccharide Utilisation Locus from Chitinophaga pinensis simultaneously targets chitin and β-glucans found in fungal cell walls. Lu Z*, Kvammen A*, Li H, Hao M, Bulone V, McKee LS. mSphere 8 (2023) e00244-23 *Authors contributed equally and share first position

I have been scientifically obsessed with bacteria from the Bacteroidetes/Bacteroidota genus for a long time. Even when I have spent time researching diverse other topics like sterol metabolism, potato pathogens, cell wall synthesis, and lignin structure, I keep coming back to work on these brilliant bacteria.

The Bacteroidota are a dominant group in the microbiomes of essentially every ecosystem where complex carbohydrates (glycans) are found – this includes the human gut, the rumen, the soil, and the ocean. They thrive in these diverse ecosystems despite difficulties like high competition from other species or low substrate concentration making it hard to grab nutrients. They do so well because they have certain adaptations that enhance their survival fitness. First among these has to be the Polysaccharide Utilisation Loci in their genomes, which we generally refer to as PULs.

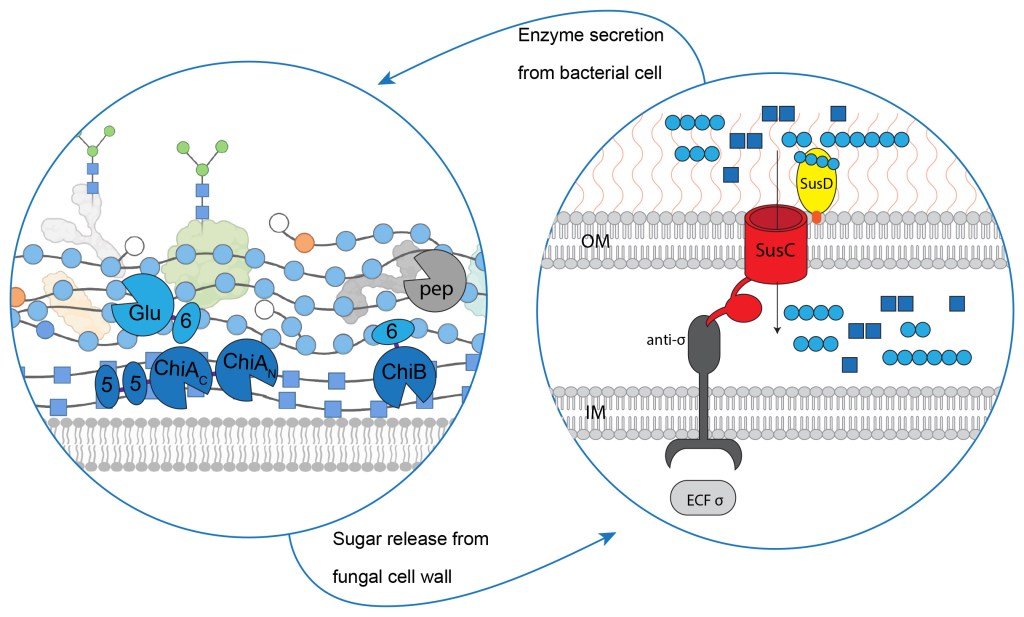

As has been written in a number of excellent reviews and book chapters (including some that I have contributed to), a PUL is a discrete contiguous set of genes that encode the protein elements a bacterium needs to metabolise a certain glycan. On the outer membrane of the cell, we find a pair of proteins called SusC-like and SusD-like proteins – these work together to recognise specific glycan structures and bring them into the periplasm (the space between the outer and inner cell membranes). The glycan brought into the periplasm gets recognised by a protein on the inner membrane, which sends a signal to the DNA. This leads to a major increase (upregulation) of gene expression for all of the genes in the PUL. Importantly, this includes genes encoding enzymes that can work together to deconstruct the activating glycan into sugars small enough to be brought into the cell and metabolised.

This system is extremely elegant. And it is an effective energy-saving tool. Many of the enzymes that are used by bacteria to deconstruct complex carbohydrates are large modular proteins, and they often have to be secreted outside of the cell to reach their substrate. This is an energy-expensive process, and it would be wasteful to secrete big enzymes if their substrate were not available. So including these genes within a PUL means that the enzymes only get produced when their substrate is present. Neat! In many cases, researchers have suggested that PULs give bacteria a competitive advantage over other species as it lets them grab onto substrates and hoard them so other species can’t access the nutrition. Rude!

The first PUL to be studied was the now-canonical Starch Utilisation System (SUS), in the lab of the incredible Prof Abigail Salyers. Examples have since been characterised that target polysaccharides as diverse as chitin, xyloglucan, xylan, mannan, and more. These PULs share a number of features – they all have the SusC-like and SusD-like outer membrane proteins, gene expression is activated by the glycan substrates of the PUL, and the enzymes encoded act synergistically to degrade that glycan. This past summer, we published an article that showcased a PUL that I find interesting because it breaks this trend just a little bit, by encoding enzymes that target two different polysaccharides. Like many of my recent and ongoing enzyme discovery projects, this PUL was first identified as a target for characterisation in a paper I published in Applied & Environmental Microbiology in 2019 (https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02231-18), in which I announced that my favourite bacterium is and will always be Chitinophaga pinensis.

Our new paper was published in mSphere in July 2023 (https://doi.org/10.1128/msphere.00244-23). The first author on the paper is Zijia Lu, who did a 60-credit Master’s thesis project in my group as a guest student from Uppsala University. Zijia was incredibly productive during her entire time in the lab and had already published two other articles that included her work (published in FEBS Journal and mBio). Her main goal for her thesis was to explore enzymes produced by Chitinophaga pinensis that may be involved in degrading or attacking the cell walls of fungi or oomycetes, principally the cell walls of plant pathogenic species. The idea was that, if we could find enzymes that attack pathogen cell walls, we may be able to use C. pinensis as a biocontrol weapon against plant disease. But first, extensive biochemistry was called for.

The PUL we were looking at encodes three enzymes, all of which contain both catalytic domains (glycoside hydrolases, GHs) and non-catalytic domains (carbohydrate binding modules, CBMs). We looked at the protein sequence and family annotation of all of these domains, then tried to produce them in different combinations to understand their activities. One enzyme (CpGlu16A) was predicted to be able to hydrolyse beta-glucans, and carried a CBM we predicted would bind the same glycan – and those predictions were right! When a CBM binds to the same polysaccharide as its enzyme partner is hydrolysing, we tend to see that the enzyme works better and/or faster, because it sticks to its substrate for longer. This was also the case for another enzyme in the PUL (CpChiA), where the GH domains were predicted to hydrolyse chitin and the appended CBMs predicted to bind chitin. Again, the predictions were accurate. Zijia did a huge amount of work to understand these enzymes, but an annoyingly persistent global pandemic broke out while she was visiting family in China, so things were put on hold and ultimately the project was not completed by the time Zijia had to submit her thesis.

In October 2021, our lab was joined by Alma Kvammen, a powerhouse Research Engineer who always had the energy to jump into new projects. She helped us complete a lot of different initiatives, including Zijia’s PUL. The third enzyme in the PUL (CpChiB) was intriguing – we correctly predicted that the enzyme domain would hydrolyse chitin, while the CBM would bind to beta-glucan. As you would expect, this means that the CBM gives the enzyme no advantage in hydrolysing chitin. But we must always remember that, in nature, polysaccharides do not exist as isolated purified molecules – they exist embedded within highly complex cell wall matrices. Chitin and the kinds of beta-glucan our enzymes are targeting are found specifically in fungi, and we think the PUL we characterised most likely targets intact fungal cell walls. Earlier work had shown how enzymes targeting pectin or hemicelluloses in plant cell walls can be made to work more effectively on intact plant biomass if they are attached to cellulose-binding CBMs, and we think our beta-glucan-binding chitinase is an example of the same phenomenon!

The last key element that defines a PUL is that its enzymes should work synergistically to break down the substrate. Alma prepared a fungal cell wall extract from button mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus) to see how the enzymes behaved when mixed together. The extract was a highly condensed material, due to the preparation process, and so enzyme accessibility was probably quite low. This meant that the release of reaction product by the enzymes was also low. Nonetheless, Alma was able to show that the enzymes do a better job of breaking down the fungal cell wall when they work together, rather than when they are alone. So all in all we are confident in saying that the Fungal Cell Wall Utilisation Locus (FCWUL) fulfils all the criteria of a classical PUL, except that it can target a more complex substrate. Next step is getting back to Zijia’s initial question – can these enzymes work together to kill a fungus? That might be a question that runs over several Master’s thesis projects…

Zijia Lu now works at EnginZyme in Stockholm, Sweden, while Alma Kvammen is working at ArcticZymes in Tromsø, Norway. Two brilliant enzymologists and biotechnologists, productive and professional in every way.

Pingback: Year in review – 2023 | Stockholm CAZyme Lab