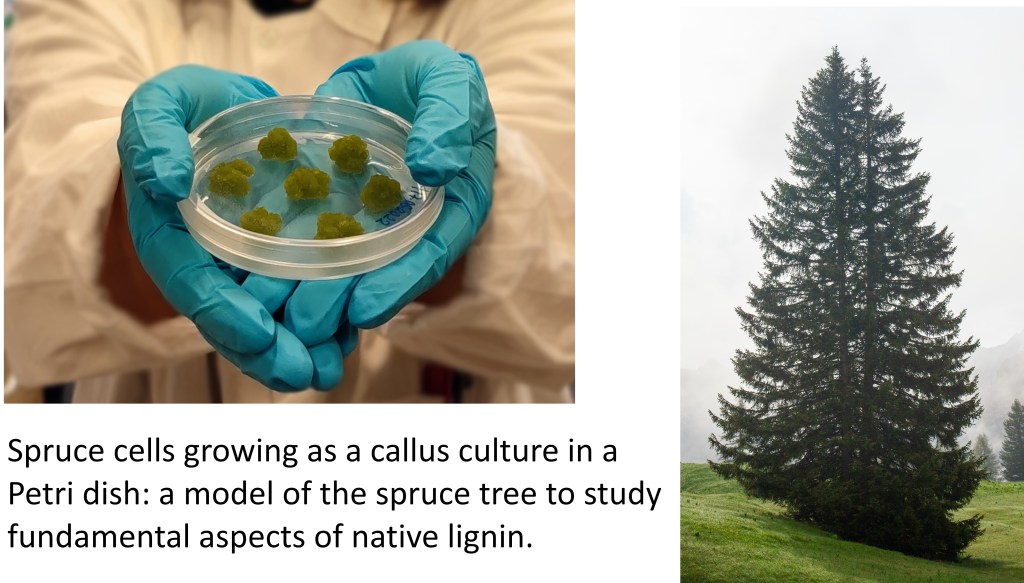

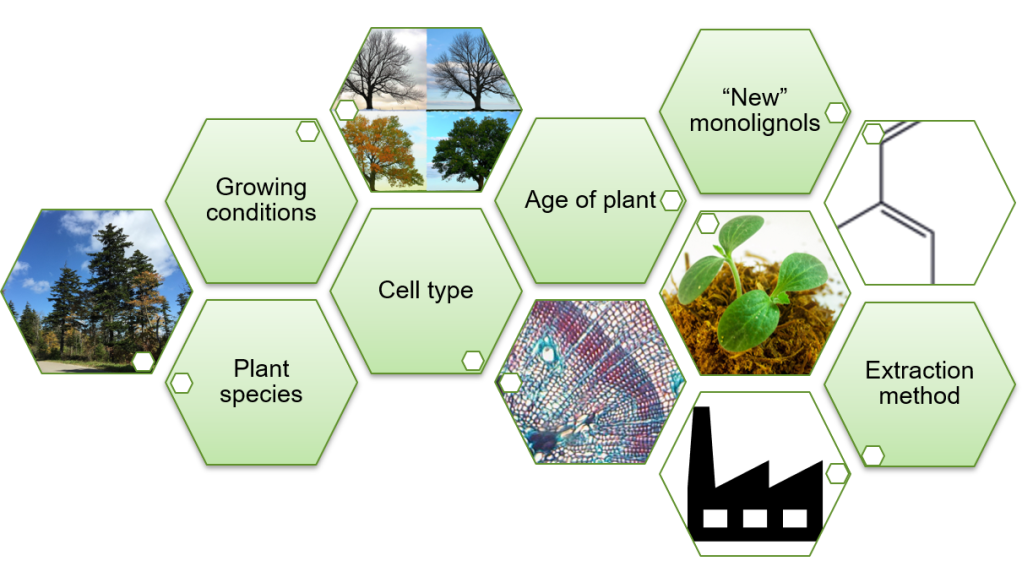

Over the years, many different protocols have been developed that enable lignin extraction from biomass, each aiming to acquire high yields while maintaining certain characteristics. The structures obtained from an extraction make the polymer useful either in specific industrial applications or for research purposes, such as to understand the fundamental structure of native lignin. The native composition of lignin varies depending on several parameters, such as the plant species. As a result, it is considered challenging to develop one universal protocol for lignin extraction that works for all types of biomass, ensuring the same lignin yield and structure. In work published in 2021 in Green Chemistry (https://doi.org/10.1039/D0GC04319B) we developed a protocol that enabled us to study the impact of a popular mechanical pre-treatment, known as ball milling, on the extractability and structure of lignin from softwood (spruce). Even though I used mild conditions throughout the sequential extraction protocol, I could extract almost 85% of the lignin in the wood, in contrast to classic protocols with typical yields up to just 50%. With detailed characterization of the lignin size and structure by size exclusion chromatography and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, we got insight into the architecture of the plant cell wall and hypothesized on what is happening to its polymers during ball milling, on a supramolecular level.

To further explore lignin extractability, we have now applied the same general mild protocol to obtain lignin from ball milled hardwood (birch), as described in our recent publication in ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering (https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.3c02977). Softwood and hardwood species differ in cell wall composition, so the extraction of biopolymers is considered to need a different approach for each type of wood. If I compare my own data on extracting lignin from a softwood and a hardwood, using this sequential extraction protocol, I actually see rather similar trends in terms of the impact of ball milling time and atmosphere on the lignin extraction yield. In this new hardwood study, we used a technique called pyrolysis GC-MS to look more closely at the impact of each step in the extraction process. Hardwood lignin has two major building blocks (units), whereas softwood lignin just has one, and we observed a preferential extraction of one specific lignin unit from the hardwood in certain extraction steps. Knowing this gives some clues as to how an extraction process might be designed to target specific lignin structural characteristics. In addition, with this protocol we got the opportunity to study some lignin-carbohydrate complexes of ether and ester type in some fractions, an excellent opportunity to discuss the nativity of these still controversial bonds. It was interesting to see that the order in which certain extraction steps were applied did not greatly affect the yield or the structure of the lignin fraction we obtained. This suggests a strong influence from the solvent system, pH, and temperature used, which, again, can inform the development of protocols that target lignin for specific applications such as surfactants and antimicrobial coatings. It also indicates that we may not yet fully understand the impact of, say, ionic liquids or acid, on intact wood biomass, as the effects of changing parameters would then be more predictable.

In order to showcase the potential for using lightly modified or “native-like” lignin in material applications, we used the fractions extracted from softwood and hardwood to prepare lignin nanoparticles (LNPs), a popular form of biomaterial being explored around the world for a range of uses. In this work recently published in Industrial Crops & Products (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.117660) we saw that the morphology of lignin nanoparticles depends on several parameters. These include the concentration of lignin, the polysaccharide content in the lignin fraction used, and the inherent chemical properties of lignin, such as its molecular weight, β-O-4’ content, lignin unit composition (S/G ratio), and hydroxyl content. There are many implications on the colloidal stability of these nanoparticles suggested by the aforementioned parameters that a more in-depth characterization of their formation mechanism might look into. LNPs are today typically formed from so-called technical lignins, a residue of the pulp and paper industry, and are being explored for a plethora of applications such as sunscreens and small molecule encapsulation. A variety of different techniques have been developed for LNP formation that offer high control of their properties and morphologies. However, our proof-of-concept study investigated the applicability of lignin fractions that come from milder lignin-focussed targeted extractions, using a green solvent system and a very simple setup. By using a ‘cleaner’ kind of lignin, we could control the experimental setup very well and analyse a number of parameters of LNP formation at the same time. Our nanoparticles also seem to be pretty stable, giving further support to the idea of using mildly extracted fractions in industry.

I am very happy that these publications derive from collaborative efforts. The project on lignin extraction from hardwood included important contributions from Gijs van Erven from Wageningen University in the Netherlands, who brought not only his expertise on pyrolysis GC-MS, but also insightful ideas on data interpretation. Also, results from the Master’s thesis of former KTH student Emelie Heidling were included in the extraction paper. Being involved in Emelie’s supervision was an important experience of my doctoral studies. I found it to be challenging and occasionally stressful, yet rewarding and extraordinary at the same time. Closely following and having even the smallest impact on the educational development of another person made me more confident that teaching is a career that I would love to follow.

The LNP project was a collaboration with Alexandros Alexakis, a materials scientist and expert in latex nanoparticles formation, and Eva Malmström Jonsson, the current director of the Wallenberg Wood Science Centre. Alexandros was a WWSC PhD student at KTH in my graduating cohort, and is now a post-doc at Stockholm University. I truly enjoyed this collaboration as it combined our independent efforts in our respective “comfort zone” fields and enabled me to learn new methods as I became more familiar with techniques that I had only briefly used in the past. Following the different approach Alexandros was taking on data interpretation and reflecting on our discussions made me realise that understanding material properties is not only about technical characterization. An important aspect is digging deeper into understanding the interactions between the components of a material and their role in structure-property relationships.

Having two more collaborative projects during my doctoral studies that led to successful publications is in itself rewarding. By bringing together diverse expertise and approaches, collaborations create results that may not have been possible from individual effort, and they also promote personal development and networking. I am looking forward to what the future holds, and I hope more collaborations are included!