Carlos Huertas Diaz is a PhD student in our group. He started at KTH in September of 2025, and his work is mostly funded by the Swedish Research Council Vetenskapsrådet. Lauren McKee is his main supervisor, and he is co-supervised by Francisco Vilaplana at KTH and Johan Larsbrink at Chalmers University, Gothenburg.

Hi Carlos, and welcome to Stockholm! Congratulations on starting your PhD programme at KTH! You finished your Master’s degree just before summer and now you’re a doctoral student – how does it feel so far?

Hi Lauren! Thank you so much for this opportunity first of all. It feels unreal: I had literally just finished defending my Master’s Thesis and a few minutes later I got the offer of this PhD position, perfect timing! It’s a huge step in my career and a big challenge, but as we have talked about, I really want to keep learning and further researching, and this is just the perfect opportunity. So far I’ve felt super welcomed, the people at the Glycoscience Division feel like family already and this creates such a nice working environment where I can totally be myself.

What has been the biggest challenge or the most unexpected thing since you started at KTH?

Honestly the most challenging part was finding an accommodation, since I had no clue that Stockholm had such a high demand for housing and you had to be registered for queues before. And now being an employee that is still also a student: that has been a big transition from only being a student, where this is a total new environment and with much more responsibilities and where the start point feels different from being in a class with many other students (where everyone is as lost as you), to sharing an office with people working on many different things (where everyone is still lost, but lost individually). However, it feels very enriching to get to know about all these new topics.

What are you most looking forward to in the coming four years?

I am so ready to learn more and be able to develop myself as a researcher! I wanted to continue studying because I still feel I have the motivation and I would really like to implement this knowledge at the same time, so a PhD was just perfect for these characteristics. It will for sure be a great challenge and with ups and downs, but I really want to dive deeper in research and be able to join the scientific community. Apart from that, traveling and exploring different facilities and working environments is something I would really like to do and I believe it can be very fulfilling, where you can meet great scientists who shape you and teach you along the way! I’m looking forward to my first conference next spring, and I hope we can plan for at least one research visit for me somewhere.

And is there anything you are particularly nervous about?

I am a bit nervous about publishing and writing manuscripts, since it’s new for me and as a mandatory part of the PhD it’s something I have respect for. I see it as a complicated process, where I will give my best to do as great as possible. I thought that I would be nervous about teaching and supervising Master students, but now I am feeling quite optimistic and looking forward to it. I think it will be real fun.

You are working now in the Division of Glycoscience, and there’s a lot to learn about carbohydrates and how we analyse them! Tell us a bit about the research project you are going to be working on.

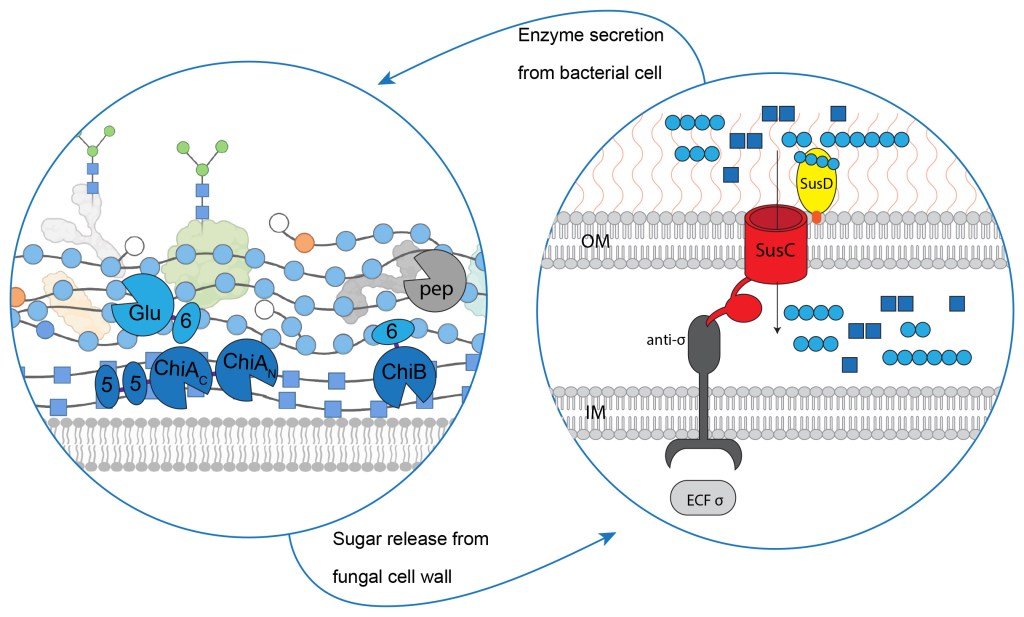

In this project we will be working on the discovery, characterization, engineering and the application of carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) of microbial origin. We are aiming to explore the diversity of these enzymes encoded by industrial and environmental microbes. The main goal is to understand their activities and stability, exploring their application for industrial processes. Many recent studies propose that non-catalytic appended accessory domains such as the carbohydrate binding module (CBM) can stabilize CAZymes, but this is not really confirmed or understood, so we will test these hypotheses. For this project we are aiming to understand these inter-domain interactions and the stabilizing effects on the CAZymes so that stable industrial biocatalysis can be achieved.

Your previous research experience was at Lund University and before that in Spain. What was the difference between working in those two places? And how do you think KTH compares so far?

In Spain I did my Bachelor’s Thesis at the Center of Molecular Biology Severo Ochoa (CBMSO) in Madrid under the supervision of Aurelio Hidalgo. Then in Lund, Javier Linares-Pastén supervised my Master’s Thesis in the Biotechnology Division of the Engineering Faculty (LTH) of Lund University. They were both amazing experiences where I could settle myself into research. The main differences I would say were the authorship scale, where in Spain the gap between students and researchers or principal investigators is greater than the one in Sweden, where I felt professors were more easily approachable and students have more freedom of creativity in their project. Moreover, in Lund the facilities of the Kemicentrum, where I was performing my thesis, were more updated than the ones in CBMSO, so of course it was more accessible where the most resources were present. Here at KTH I see it so far as very similar to Lund University, with a super friendly and uplifting environment, where I can see myself improving as a researcher with great facilities and infrastructure.

A few short questions to get to know you…

What is your favourite kind of food? Empanada (I think the translation would be meat pie).

Do you prefer to read books or watch movies? Movies, but a good book is always better.

What is your favourite animal? The galaxy frog.

What is the best advice you’ve ever received? I live with this quote in my mind “journey before destination” where someone added “but in company”.

What skill would you most like to learn? Further understanding mass spectrometry or nuclear magnetic resonance would be very cool.

Thank you Carlos for telling us about yourself – we are so glad to have you join the team!!